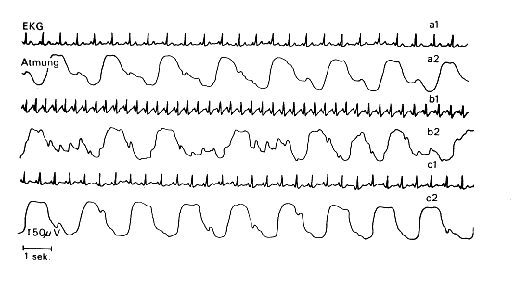

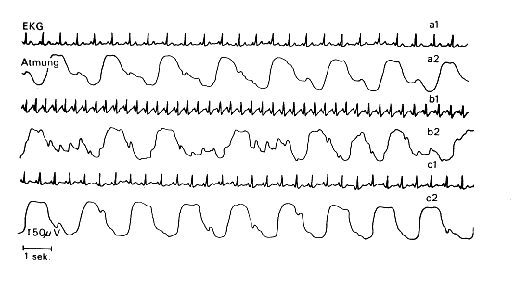

During the early 1970s, Gerhart Harrer did an extended, four-part study on the famous German conductor Herbert von Karajan. First he measured the EKG, breathing, and GSR of Karajan and his student while listening to a recording of Beethovenís Leonore Overture. Certain features emerged in the signals of both Karajan and his student that could be traced to the structure of the music. Then he gave both subjects a tranquilizer and measured the same signals while the subjects listened to music. After the tranquilizer was given, the musically-affected features in the signals were greatly reduced. However, both Karajan and his student did not notice any difference in their experience of the music between their tranquilized and untranquilized states, which suggested to Harrer that their internal experience of the music diverged significantly from their physical experience. These signals are shown below:

Lines a1 and a2 represent one subjectís EKG and breathing signals at rest. Lines b1 and b2 show the same signals while the subject listened to music on headphones, demonstrating irregular features that Harrer attributes to the music. Lines c1 and c2 show the same signals while the subject listened to music, after he had been given tranquilizers.

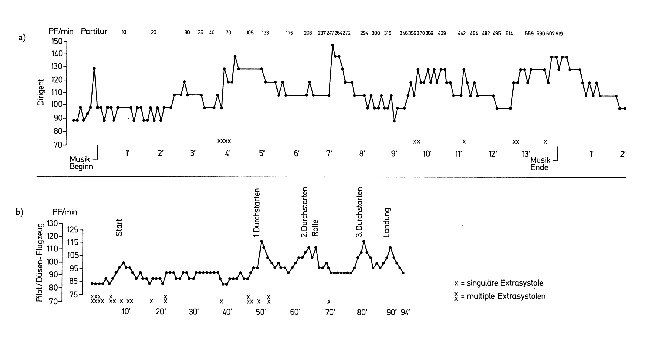

In a second study, Harrer outfitted Karajan with EKG, pulse frequency, temperature, and breath sensors, which transmitted their data wirelessly to a computer. He measured Karajanís signals during a recording session of the same Beethoven overture the with the Berlin Philharmonic for a television film. The strongest changes in those signals correlated with the moments in the music that Karajan said moved him emotionally the most. Thirdly, Harrer played a recording of the Beethoven overture for Karajan while he wore the same sensors. Qualitatively, the sensors yielded similar features at similar points in the music. However, quantitatively, the signal strengths on all the channels were weaker. Finally, Harrer put an EKG sensor on Karajan during two different activities: flying a plane and conducting the Berlin Philharmonic. While piloting, he performed a dangerous maneuver three times in succession; he approached as if to land, and then took off again. He also accompanied the second one with a roll. Each time he did this, his pulse increased markedly. Also, he was subjected to a second pilot taking over the controls at unannounced times. However, despite all the stresses of flying under such unusual circumstances, his heart rate averaged about 95 beats per minute and never exceeded 115. However, when conducting the Beethoven Leonore overture with the Berlin Philharmonic, his heart rate averaged 115 beats per minute and peaked at 150. The range of variation while conducting is almost double that of the range while piloting. While Harrer acknowledged that the movements are greater for conducting than for piloting, he determined that a great deal of the difference could be attributable to the fact that his piloting heart beat was in reaction to stimuli, whereas in conducting he was specifically and premeditatedly expressing a signal.

The below figure shows the systolic activity in Karajanís EKG signal during both activities. The upper graph gives Karajanís heart rate while conducting, with measure numbers above to show its relation to the musical score. The lower graph shows his heart rate while piloting, with the three risky maneuvers clearly delineated in sharp peaks.

Harrerís study is, as far as I know, unique in the literature; his is the only other work to put sensors on a working conductor. Unfortunately he only published the EKG signals from Karajan; it would be interesting to see if the other data is still in some recoverable form. Harrer is now retired from his position as chairman of the Psychology Department at the University of Salzburg.