There appears to be a kind of ‘predictive’ phenomenon, whereby our conductor subjects indicated specific events on the beats directly preceding the intended ones. This is often discussed in the literature on conducting technique, as evidenced by a sentence in one of the most influential treatises on conducting: "in a sense, all conducting is preparation – indicating in advance what is to happen." Also, in another important text, the author urges conductors to "bring the left hand into play one beat before the cue-beat and make a rhythmic preparatory beat leading to the cue. These are both good for improving your ‘timing.’" In a third treatise, Adrian Boult wrote:

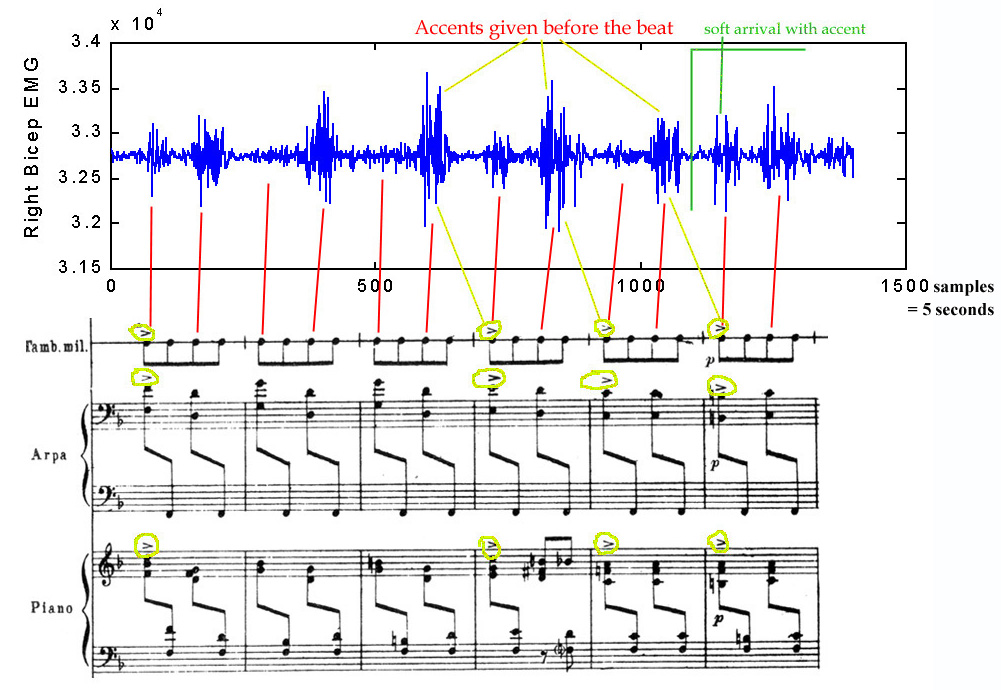

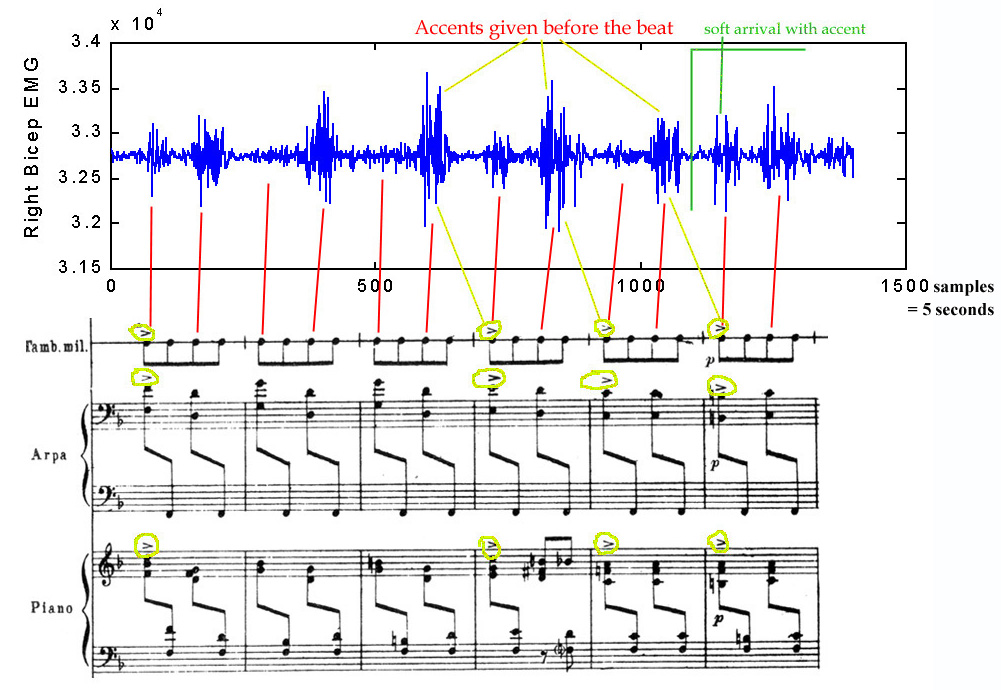

The red lines show how the EMG signals line up with the beats in the score, while the yellow lines show the relationship between the conducted accent and the accent where it is to be played. The green line around sample 1100 represents the barrier in-between the first section, marked forte (loud), and the second section, marked piano (quiet). The reduced amplitude of the EMG signal right before the separation line could indicate an anticipation of the new, softer loudness level. One aspect of this segment that I cannot account for is this conductor’s large signals in places where accents are not indicated, such as in the first two measures. Perhaps P1 is trying to perpetuate the pulse of the music or has chosen to emphasize the downbeats even though accents are not written in the score.

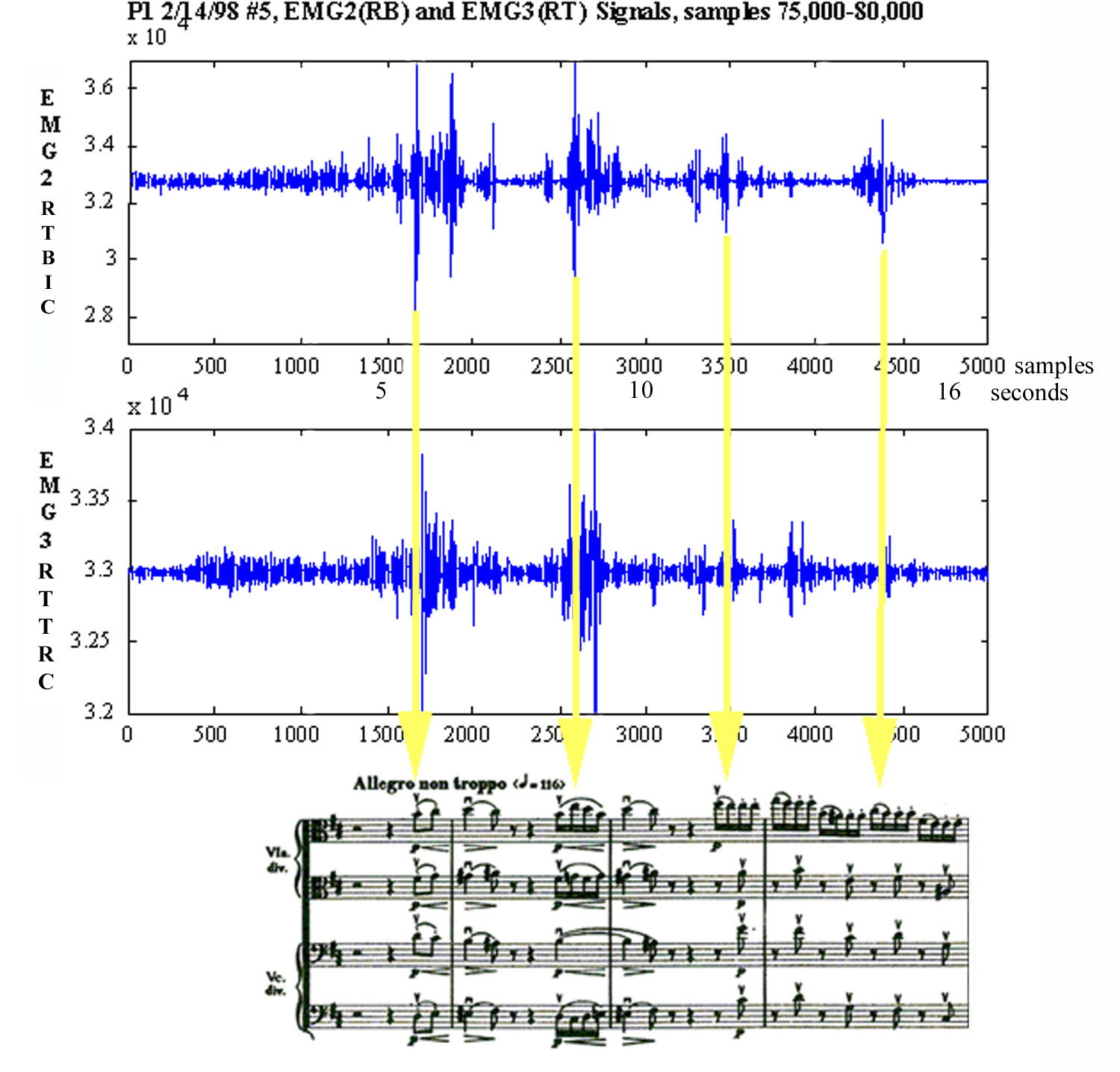

Another example demonstrates this phenomenon with an entirely different piece of music -- the first four bars of Tchaikovsky’s Symphony no. 6, in the Allegro non troppo movement. In this case, an emphasis is intended at the beginning of measures 2, 3, and 4. This emphasis is consistently given on the last beats of measures 1, 2, and 3:

Perhaps the prevalence of predictive indications can be explained biologically by the presence of a fixed delay in our perceptual system. It has been shown, although theorists do not always agree on the amount, that there is a fixed minimum amount of time that it takes for a human being to respond to a stimulus. Any incoming sensory signal must be transduced to electrical impulses, transmitted to the brain, interpreted, and acted upon. So it would automatically take some time for an orchestra to adjust to unexpected changes, and therefore having the control signal be a beat ahead probably reduces the number of errors. The metacommunication of giving the expressive indications for a beat during its previous neighbor possibly optimizes the result, given the fixed biological constraints.